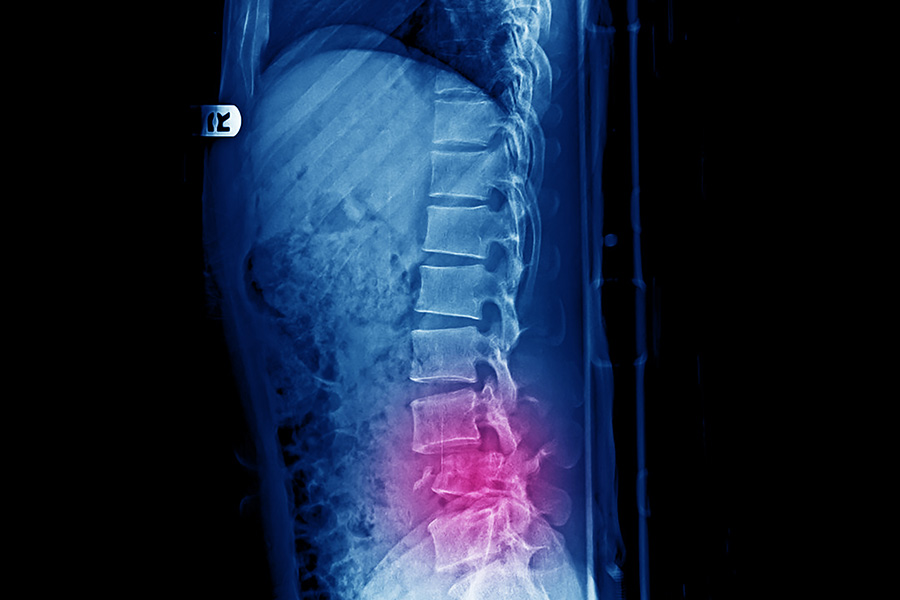

Vertebral Compression Fracture (VCF)

Explore Our Approach

What Is a Vertebral Compression Fracture?

A vertebral compression fracture happens when one of the bones in your spine collapses.

This can result from osteoporosis, other bone-weakening conditions, trauma, or a combination of factors.

Sometimes they happen after a fall or accident, but in weakened bone, even everyday movements — like bending forward, lifting, or coughing — can cause a fracture.

Even if a fracture appears “old” or “healed” on MRI, it may still cause pain if there is instability or tenderness on exam.

Why Vertebral Compression Fractures Cause Pain

Vertebrae are load-bearing structures.

When one collapses, abnormal motion at the fracture site, strain on surrounding muscles and ligaments, and irritation of pain-sensing nerves in the bone can all occur.

Postural changes from the fracture can add stress to adjacent joints and discs.

A fractured vertebra contains pain-sensitive nerves and baroreceptors that respond to movement and pressure changes.

Protective muscle spasm, meant to reduce load, can actually compress the affected bone, increasing axial loading and worsening pain.

Why Vertebral Compression Fractures are Sometimes Overlooked

There are several reasons that fractures are missed.

The most common are lack of health-care provider (HCP) expertise, incorrect training, not performing a physical exam on the spine and missed diagnosis by radiologists.

Other causes are limited accuracy of imaging, and HCP apathy..

Lack of expertise mainly occurs because identifying and treating VCF is not a focus in medical training or a priority for large health-care system decision makers.

This is despite the fact that VCF is the most common fracture in man.

Because some studies have estimated that 2/3 of VCF heal on their own, there is a cognitive bias against VCF being a source of pain.

The diagnosis is usually only suspected in the most extreme and obvious causes, such as someone with an established diagnosis of osteoporosis becoming wheelchair-bound and having a fracture with a textbook appearance on imaging.

HCP are taught that MRI is highly accurate and almost given a cult-like belief in the accuracy of MRI.

Yet there are no scientific studies evaluating the accuracy of using STIR MRI for detecting VCF.

There are studies, however, that show that radiologist’s reports miss almost all (85%) of VCF on imaging.

Not only are human radiologists imperfect at detecting fractures, when fractures are identified by a radiologist, they often call them old and healed if they don’t ‘light up’ on MRI–a phenomenon that on happens about half the time in a clinically symptomatic fracture in Medicare aged patients (Lensig).

Since HCP are trained that 2/3 of fractures heal on their own, they are also trained that most VCF they see are not symptomatic.

If they clinically suspect a fracture, they may send for an MRI.

If that MRI report is read as an “old” fracture by a radiologist who never saw nor examined the patients, the HCP will assume it is correct.

At this point, when an initial diagnosis is made uncertain by a test, the HCP should go back to their initial diagnosis and see if they missed something.

Unfortunately this doesn’t happen often in 2025.

Most providers rely only on imaging to make the diagnosis, rather than history and physical examination.

Based on the number of fractures that MRI misses (46%), compounded by the high likelihood that a radiologist will not mention a fracture in a report (85%), imaging miss rates may be as high as 92%!.

That means that MRI is ALMOST ALWAYS going to give you an incorrect answer.

Unfortunately, you’d be better off flipping a coin because multiple studies have shown that a majority of vertebral fractures are missed in radiologists reports.

Very Few Vertebral Fractures Are Called By Radiologists

You read that right.

In fact, as ridiculous as it seems, the standard of care in medicine is to either miss or underreport vertebral fractures on imaging.

About 85% vertebral compression fractures are missed in CT reports by board certified radiologists (Carberry, 2013; Bartalena, 2009).

A metanalysis by Bartalena also showed that radiologists are–incredibly–actually getting worse at diagnosis fractures.

According to Bartalena et al. (2010), “Incidental vertebral compression fractures in imaging studies: Lessons not learned by radiologists”, published in World Journal of Radiology (2010; 2[10]: 399–404), a review of the literature found an overall average reporting rate of only 27.4%.

That means that radiologists miss at least 75% of all fractures, with even worse rates in multidetector CT (only call about ~8.1% vs ~41.1% on x-rays).

Importantly, they noted that more recent studies showed even lower reporting rates than older ones, demonstrating a worsening trend over time.

Said another way, we radiologists are terrible at diagnosing fractures and only appear to be getting worse with time.

No Science Supports MRI Use To Diagnose Vertebral Fractures

Yes, we often see fractures on MRI.

Sometimes they even light up.

But in over 3,000 english language articles on vertebral compression fractures, there are actually zero (0) published studies even assessing the accuracy of STIR MRI to detect thoracolumbar fracture.

The only time STIR accuracy for spinal fracture has been looked at at all was in the neck.

A single cervical spine study by Lensing et al. found that MRI missed approximately 50% of C2 fractures in older patients and 20% in younger patients.

The bottom line is that the only scientifically proven, high sensitivity method of clinical fracture detection is the physical exam (Lensing 2014; Brown 2004; Langdon 2010).

As such a “normal” MRI report or one that mentions “old fractures” does not exclude clinically important vertebral fractures, particularly in the setting of osteoporosis or subtle injury mechanisms.

A careful physical exam often reveals tenderness or mechanical signs missed on scans.

In many cases, imaging such as MRI will label a fracture as “old” or “healed,” especially if there’s no bone marrow edema.

However, pain can still come from these fractures if there’s instability or persistent tenderness on exam — regardless of how long ago the injury occurred or how it appears on imaging.

An MSKIR Perspective

Diagnosis is guided by history, targeted examination, and supplementing with imaging correlation.

When clinical findings indicate, treatment aims to restore stability and reduce pain.

If a fracture is tender and correlates with the patient’s symptoms, it may be considered for treatment based on medical necessity.

Diagnosis is guided by a detailed history, targeted examination, and imaging correlation.

When clinical findings indicate, treatment aims to restore stability and reduce pain.

Vertebral Compression Fracture Treatment Goals

Creating a cavity in the spine

Creating a space for the bone glue to be placed also disrupts internal blood vessels in the fractured vertebrae, reducing leakage into the systemic circulation.

After treating thousands of fractures, I can attest that this is the key benefit to cavity creation or kyphoplasty, not fracture reduction.

Stabilize the fracture

We inject polymethylmethacrylate–also known as PMMA, bone glue or bone cement–into the fractured vertebrae, creating an internal cast that stops the microscopic and macroscopic movement that causes pain.

Assess and address underlying bone health

Vertebral augmentation is a miraculous procedure that is highly effective at treating the pain from a vertebral fracture.

However, in order to reduce the risk of future fractures, a more holistic approach is needed including pharmaceutical treatment and risk factor reduction.

Measuring bone mineral density (BMD) with DEXA and bone quality with Trabecular Bone Score (TBS) are complementary ways to assess overall bone health and to monitor long term treatment response.

Prevent future fractures

In addition to the above, focusing on fall prevention, assessing fall risk in the home, rehabilitation to improve core strength and balance control as well as activity modification are essential ways to reducing future fracture risk.

Request a consultation » Call today! (918) 260-9322

Office Location

Dr. James Webb & Associates, 6550 E 71st St #200, Tulsa, OK 74133